Biography

Diego Rivera Biography (1886-1957)

Child Artist

Many diverse and opposing "facts" have been written about this artist, including major historical discrepancies scripted in his own autobiographical writings. There are more myths about him thought to be true than the truth itself, and Diego, the spellbinding storyteller, was behind most of this spun life.

Diego Rivera was not your ordinary human mortal in terms of physical size, imagination, creativity and, most of all talent. He was determined to create his own legend so people would be sure to know just how great he intended to live, think and paint. What did he probably consider to be his three most important assets?

Large, Large, and Large.

He lived large, he dreamed large and he painted large!

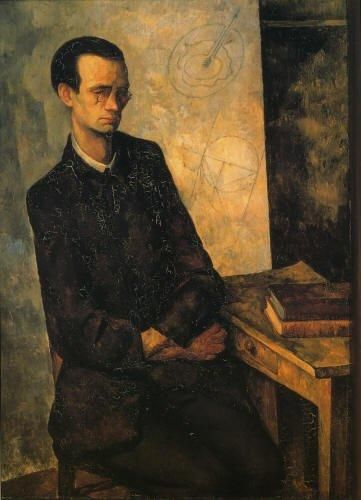

Self Portrait, oil on canvas, 1886

Self Portrait

The first glimpse we see of Diego’s mythmaking enhancements on his life story begins with the subject of his birth name. He and his twin brother, Jose Carlos Maria Barrientos Rivera, were born on December 8, 1886. His parents gave him the birth name of Jose Diego Rivera but he always insisted that his full name at birth was Diego Maria de la Concepcion Juan Nepomuceno Estanislao de la Rivera y Barriento Acosta y Rodriguez. His twin died eighteen months later. It would seem we have the beginning of a legend in the making.

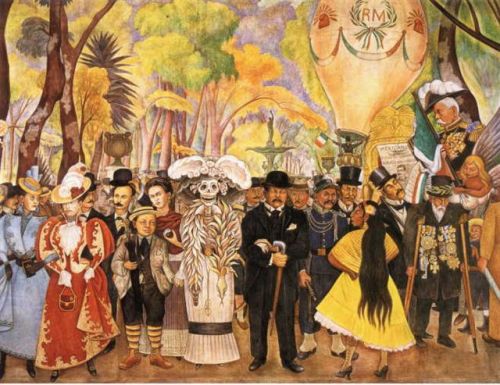

Diego was born in Guanajuato, Mexico, an old silver mining town founded in 1559. The town is built on the slopes of the Sierra Madre and the P’urhepecha translation of the town’s name is “hill of frogs.” Perhaps that is why the frog became a personalized signature in several of Diego’s paintings of himself as a boy, such as the one seen climbing out of his coat pocket in his last great masterpiece, Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park, Museo Mural Diego Rivera, Mexico City.

Diego started to draw at the age of three, as he has said about himself, "Just as soon as I could get my short little fat fingers around a pencil, I was drawing on everything. So I wouldn't destroy the entire house, my father hung canvas over the walls and floor in my room and I just never stopped drawing." He started to read at four and had an endless curiosity about the inner workings of every gadget he could get his hands on, forever taking them apart and putting them back together again.

His father, Diego Rivera, was a criollo, a person born in Mexico but descended from European ancestry. His family was one of the wealthy early 18th Century aristocrats of Guanajuato but by the time Diego was born, the silver had played out and they lived a rather shabby, yet, genteel lifestyle. Nonetheless, his father had a decent library, was a schoolteacher at the time of Diego's birth and would later become employed in governmental administration positions in Mexico City.

Senior was a political liberal and secular Freemason. He was very aware and greatly concerned about the rural poverty that left eighty-five percent of all Mexicans illiterate. Diego spent a great deal of time with his father and these shared feelings were the source of Rivera's enormous compassion for the impoverished masses of Mexican Indians. Later in life, in all his Mexican art, he would portray them with dignity and grace. He honored them as descendants of the mighty Mayans and Aztecs.

His mother, Maria del Pilar Barrientos, was a mestizo, part European, and part Indian, a devout Catholic, such as ninety-five percent of the Mexicans at that time. Her family was considered respectable middle class. She was also one of the few mestizo women to be educated and went later to the state school of obstetrics and worked as a midwife. Diego claimed his family was dirt poor and his mother could neither read nor write. This was pure storytelling probably done to create an image of "a poor disadvantaged boy, heroically struggling, destined to conquer the world."

Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park, 1947-1948

Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park, 1947-1948, detail

Diego as a Young Boy with Frog in Pocket

Art Academy Student

In truth, he was quite spoiled, dropped out of all three of his parents’ chosen schools and demanded to be enrolled in the San Carlos Academy of Fine Arts at the age of ten. He started out at the finest young adult man’s art school in Mexico as a frog eyed, fat boy in short pants and with all kinds of disgusting little slimy things boys like to carry around, crawling out of his pockets. He ended up, six years later, graduating at the top of his class, destined to become San Carlos’s most world renowned artist. This is the stuff that legends are made of and it’s all fact. Diego’s artistic mastery was the only one consistent real truth in all his life.

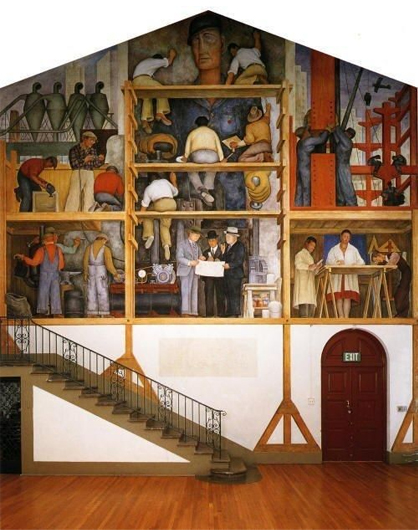

The rigid traditional perspective drawing instructed at San Carlos would turn Diego into the finest draftsman among all of his 20th Century peers. It drives his success of the tromp l’oeil in his mural work. The deftness of his pure linear draftsmanship lies beneath all his seemingly simplistic folk art paintings. He was most strictly instructed in the Golden Section, the ancient pseudo-scientific theory regarding mathematical rules of proportion. Forever, Rivera’s adherence to rules in art would distinguish his work from the Post Impressionist artists. Diego owes much of his achievement to this rigorous and rational training he received during those six years at the academy.

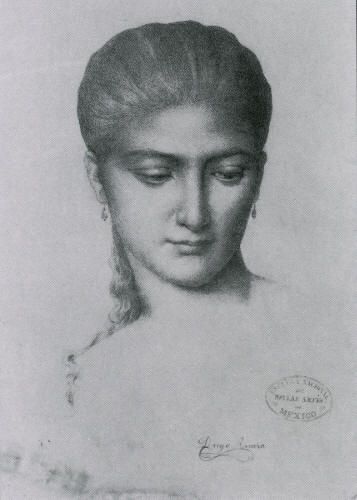

Sketch of Head of a Woman, 1898 done at age 12 at school

The Making of a Fresco, a trompe l'oeil within a trompe l'oeil, San Francisco Art Institute 1931

The most consequential wisdom garnered from San Carlos, that would forever mark his art, was the knowledge of the greatness of the pre-conquest Indian civilizations who lived and ruled in Mexico centuries before Cortez stepped foot onto their land. Rivera painted a lot of easel art to pay for his avid collecting of Pre-Columbian art. In his later easel paintings he even worked on multiples of six at the same time, claiming it was a skill he had learned from watching the mass-production on Detroit’s auto assembly lines.

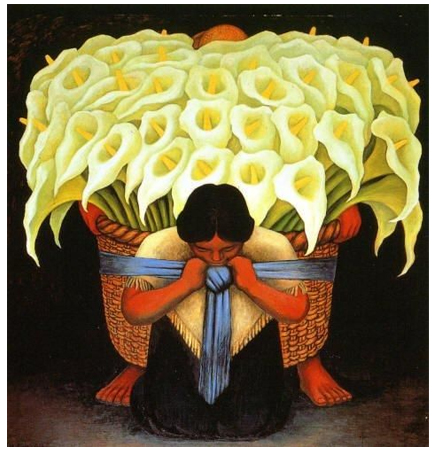

Nude with Calla Lilies 1944

Peasants 1947

Flower Seller 1942

European Tour

Upon graduating in the spring of 1906, Diego was determined to go to Europe to study the Old Masters as well as meet the avant-garde European artists of the day. Through his father's connections, but not his political allegiance, Senior was able to get his son a scholarship from the Porfirian government who were in power at that time under the dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz.

Diego chose not to go directly to Paris as most other émigrés had done, so instead, he sailed to Spain, arriving on January 6, 1907. He would stay to study and paint there for two years. He was so absorbed in Goya's paintings that his own style at that time began to emulate this great Spanish artist. The other renowned artist whom he studied intensively was El Greco.

All of the Old Masters he absorbed while in Spain can be seen emanating later from Rivera's grand murals. In his own life time, the name Mural and Diego Rivera would become synonymous. The seed of his majestic murals' success was undoubtedly planted there in the soil of Spain.

While living and touring the Spanish countryside, he was industrious as he would always be, painting, earning a living and sending his canvases home to oblige his Mexican patronage. His accomplished paintings such as the Old Stone and New Flowers show the skillfulness of his talent, but later in life, Diego believed his Spanish pieces to be the worst of his life, pictorially pleasant, at best.

Visiting Paris and London

He longed for a revolution in his art and felt he could only discover this in Paris so in the spring of 1909 he headed north. He moved into the Bohemian enclave known as Montparnasse which was filled in those days with rebel artists. Diego spent endless hours in the street cafes, sketching and arguing about "True Art" with his fellow comrades, who had come from the four corners of the globe to change the world of art.

During this year he spent much of his time studying at the Louvre Art Museum and entered his art in the academic French Salons but they took little notice of his current work. He met and fell in love with a young Russian artist, Angeline Beloff. There was serious talk of marriage, certainly more so from the involved woman's perspective than from his own. But revolution was brewing back in Mexico and he felt he had to return there to ensure the continuance of his scholarship monies. One can almost hear Diego's windy sigh-of-relief as he made his escape across that wide ocean.

House on the Bridge 1909

portrait of Angeline Beloff 1909

Mexican Revolution

Back home in 1910, the tumultuous Mexican Revolution was well under way but Rivera took little notice. He was too busy preparing his first one-man art exhibit which was concocted by President Diaz for the sole purpose of propagandizing his corrupt Mexican regime. Years later, Diego would claim to have personally championed the rights of the poor suffering masses but there is no evidence to substantiate this claim or his even more incredulous claim of actually taking up arms and fighting with the heroic guerrilla, Emiliano Zapata. Diego would have a very financially successful exhibition and return to Paris to sit out the fighting, far away from his fellow countrymen.

He would later paint the great revolutionaries in his great revolutionary art. But was Diego Rivera a Revolutionary?

Never, this was one of his most gargantuan myths.

Notre Dame de Paris 1909

Breton Girl 1920

Rivera the Cubist

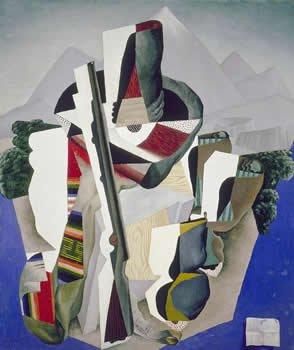

Diego returned to Paris in mid 1910 and stayed until 1920. At last his work began to undergo major shifts. He was totally immersed in Cubist art by 1913. Pablo Picasso, the inventor of Cubism, went to Rivera, not the other way around, as most people would surmise. Picasso recognized Rivera's innate understanding of the Cubist theories on the canvases Diego was producing during this period. They became best friends and worked together for over four years. The mathematical rules Rivera had learned at the San Carlos Academy transformed him into one of the world's most acknowledged great Cubists. As Diego's fame grew as an artist so did his ego. He became an outrageous braggart, spinning ever increasingly fantastic tales about his cannibalism and his heroic feats in faraway Mexico.

Zapatista Landscape 1915

"Diego was a man of the emotions," Ehrenburg, the famous Russian writer, would tell about him in later memoirs, "and if sometimes Rivera carried to absurdity the principles he cherished, it was only because the engine was powerful and there were no brakes."

Rivera, with wounded feelings, accused Picasso of stealing his own Cubist inventions, and in the year 1917, left Cubism behind forever. He said he found it too restrictive of free expression. He did paint extraordinary Cubist pieces such as his most noted masterpiece, Zapatista Landscape (The Guerrilla).

During his European years, he moved back and forth from Spain to Paris and Angeline became his common-law wife with whom he had a baby boy, Diego, Jr. born in August 1916, who died fourteen months later from the influenza, living alone with Angeline, without proper food and medicine. It seems that Diego had taken up with another Russian émigré artist, Vorobieff-Stebelska, nicknamed Marvena, while Angeline was in the hospital giving birth.

As if that were not enough of an insult to tragic Angeline, this new mistress also gave Diego a baby girl, Marika, but he would never claim this child as his own. He returned to Angeline, yet it seemed an empty gesture on his part. Through all of this personal mayhem, Diego's painting underwent another major shift and he returned to a more naturalistic form of painting with his discovery of Cezanne and Rousseau.

The Mathematician 1918

Portrait of Jean Cocteau 1918

The Great Mexican Muralist

By 1921, Diego was weary of Paris and Angeline. He longed to go home. The Mexican Revolution was over and Alvaro Obregon, the greatest general of the war's victors had been elected President of Mexico.

New educational programs swept in with this newly enlightened government. Rivera, along with other well known Mexican artists, were invited to paint massive wall murals throughout Mexico for the grand purpose of uniting all its multi-race citizens into a Country of One. Mexico was determined never again to suffer the inferiority complex of a colonized nation.

Before he sailed for Mexico, Diego took a detour through Italy to learn everything he could about fresco painting. This Italian trip was a good investment of his time because the next gun to be fired in Mexico was not for the Revolution of Politics. It was for the Revolution of Art. The gunshot to be heard would signal the start of the great mural race and Diego was now set to be at the head of the pack.

When Diego arrived home in June, 1921, thousands of new schools were being built, millions of books were being distributed and the illiteracy rate dropped by thirty percent within four years. This new free-spirited liberal government, however, needed a more effective media than books in which to sell their Glorious New Nation's story. After all those guerilla victories, the vast majority of their ethnic population still could not read or write.

Into Mexican history walks a man by the name of Jose Vasconcelos, the newly appointed Minister of Education. He is a visionary, like none seen before in his country. In the early 20th Century, film was a phenomenon on the horizon of discovery but Vasconcelos had the futuristic insight to realize that "a picture is worth a thousand words." Diego Rivera is bent on becoming his new best friend. The rest is history as we can look back in hindsight and know why the great Mural Renaissance of Mexico was born.

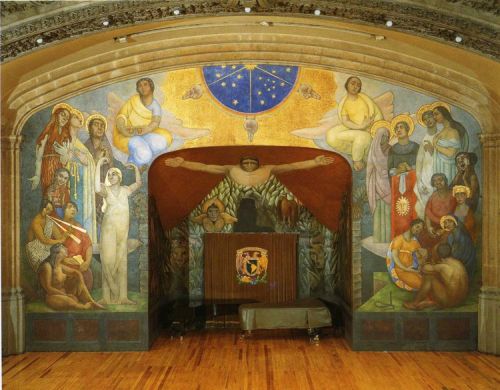

Rivera's first public mural was the Creation, painted in two stages of time.

It is critical for anyone who wants to know his art to take a close look at this mural. It is not his best by far but more than any other work it reveals a staggering change in his visual imagery. The sides and top of the arch were painted first, based on a universal life theme given to him by Vasconcelos. Diego was not happy with it, though he would never admit it.

He took a break from the painting so he could take a trip into the Yucatan wilderness. He became captivated by the primal beauty of the organic nature he experienced there. He walked out of that jungle with a pair-of-eyes that would rarely perceive images in a realistic 3rd Dimension again. He returned to paint the center niche of the mural.

The limited space of this biography will not allow us to talk about all the artistic elements behind this amazing transformation. You just have to look at it and you will instantly think that two different artists must have painted on this wall.

Creation 1922-1923

Entering the Mines, 1923, Scenes of Ministry of Education Cycle

Diego Rivera became the "King of the Hill" of Mexican iconography, and deservedly so. Everyone watched and studied Diego as he became highly skilled in this ancient art and cleverly invented many of his own techniques to make the paint behave on the plastered walls the way he wanted it to.

Today, one can become exhausted just trying to view the thousands of square feet of magnificent imagery that he inexhaustibly painted throughout his beloved country. We show you now a mural that took him over four years to complete and is universally believed to be his finest Mexican Mural. From a 21st Century mind-set, it is hard to imagine that any artist would have the endurance to accomplish such a feat. His one-hundred and twenty-eight panels at the Ministry of Education depict the history of all the Mesoamerican and European peoples, struggling to build a utopian future, summiting in a new heroic image of El Grande Mexico.

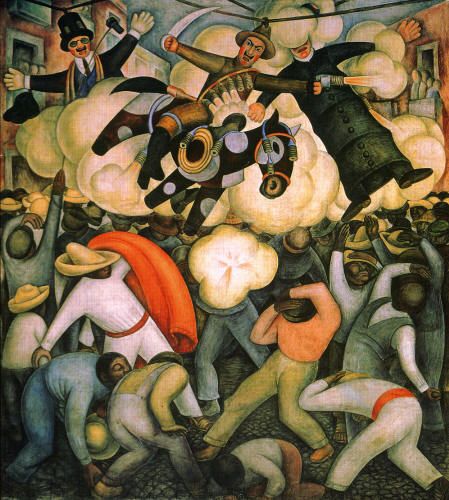

The Burning of the Judases, 1923-1924, Scenes of Ministry of Education Cycle

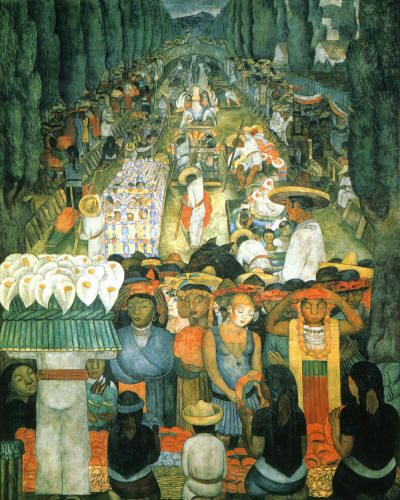

Friday of Sorrows on the Canal of Santa Anita, 1923-1924, Scenes of Ministry of Education Cycle

Ribbon Dance, 1923-1924, Scenes of Ministry of Education Cycle

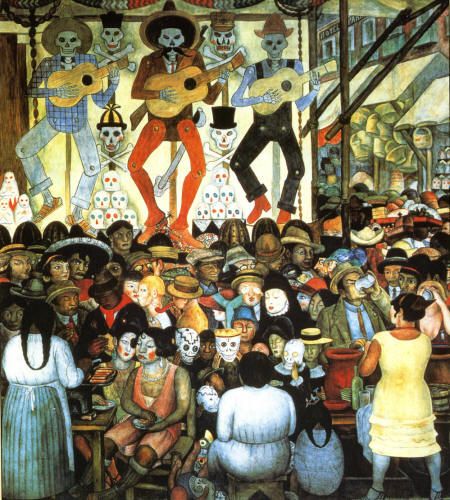

Day of the Dead City Fiesta, 1923-1924, Scenes of Ministry of Education Cycle

The Aztec World, 1929, National Palace

From the Conquest to 1930, 1929-1930, National Palace

Party Comrades in Marriage

As Diego was becoming a famous international artist, his social and political life was every bit as colorful as his professional one.

Diego Rivera was a Marxist idealist, like many young intellectuals of the early 20th Century, so it was natural that he should choose friends who shared his beliefs. The Russian Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 had transitioned Marxism into Communism so Diego formally joined the Mexican Communist Party at the end of 1922. His first wife whom he married in 1923 was also a Communist who was introduced to him by another young Communist female friend of his.

Guadalupe Marin, nicknamed Lupe, shared more with Diego than just his political beliefs. She was an exotic beauty possessed with wild emotions. Unfortunately her violent jealousy of Diego was even more than his passionate nature could eventually bear. On more than one occasion, she tore up his drawings in a fit of rage when Diego paid the slightest attention to other women. In the beginning, there is no doubt, that Diego provoked Lupe for his own amusement. Even jealous of his love for Pre-Columbian sculpture, in a moment of high drama, she ground up a prized statue and fed it to him in his soup. As time wore on, however, he grew tired of it and later said, "Lupe was a beautiful, spirited animal, but her jealousy and possessiveness gave our life together a wearying, hectic intensity."

They had two daughters Lupe, born in 1924 and Ruth, born in 1926.

Throughout the 1920's, their house became the meeting place for all the young and rebellious liberals of Mexico City. They spent long nights planning the importation of the Marxist-Leninist ideology into Mexico. These young intellectuals, many who had fought in the war, felt the Mexican Revolution did not have the ideology it so desperately needed to create a nation of equality and justice for all. They, like many young intellectual Communists in the United States, trusted the propaganda being broadcast to the world from the Soviet Union. They actually believed writers and artists were living and working in a thriving socialistic utopia. Because he was older and had knowledge of Russian, he was elected to the Communist Executive Committee. In reality, he never had time to contribute to the cause other than as a figurehead at parades, the part he best like to play. His art was always his only master.

The third reward to follow after fame and money for a man like Diego Rivera was beautiful women. He was commissioned to paint a nude mural in Chapingo for which he used not only Lupe as a model but also Tina Modotti, an elegant Italian woman with a modern day's attitude toward sexual promiscuity. Diego had never painted his female portraitures nude before but after Chapingo his portrayal of women, even if fully clothed, would forever be voluptuous. When Lupe saw herself painted in the mural at nine months pregnant and saw Tina painted as a sultry beauty, she knew she had been betrayed, both personally and artistically. As Lupe railed at Diego, he was scheming on how to get away.

Revolutionary Celebration in Soviet Union

Due to his world-wide fame as a Communist artist, Rivera was invited to participate in the 1927 Soviet Union's tenth anniversary of their October Revolution. Diego saw this as his chance to make a second sea escape across the same wide ocean, only this time he was heading east instead of west. The marriage to Lupe was over.

Rivera spent eight months in Russia seemingly unaware of the fear driven Communist power. He sketched over three hundred drawings of the workers' May Day parade. His watercolors are filled with a feeling of lighthearted gaiety completely belying the reality of Stalin's bludgeoning of his Marxist ideals. He tried to paint murals but was completely stymied by the insistence of his comrade assistants that the themes had to be decided by committee. That should have waved a red flag in his face as big as the ones he was painting in all those proletarian marches. He seems to have fallen out of favor with Stalin and in the dark of night, May 2, 1928, the commissar of education came to him and warned him to leave the country at once to avoid arrest. He left swiftly with no good bye to his mistress.

Diego's mural art was changed after Moscow. He blamed the atrocities committed in the Soviet Union on Stalin, not on a failure of the Marxist-Leninist ideology. He never acknowledged the brutality of Lenin in the first war years. He was so far away, living upon a much larger globe than the one upon which we live today. Perhaps, Russia wasn't close enough for him to see it, to believe it. But his art does not lie. It's as if he turned off the light in his paintings. His Communist propaganda art that followed is unimaginably dead. Rivera was blinded forever to the horrific realities of Communism in practice. But he refused to let go of his belief that Marxist ideals could still, some how, save the Mexican Revolution from its own corrupt betrayal of its own people.

Was Diego Rivera really a Communist? Let's answer it this way: If Stalin would have been a Mexican, Rivera would not have been a Communist.

Diego Rivera

Diego returned to Mexico in June 1928 and resumed painting his murals at the Ministry of Education. Free of marriage, he roamed the social clubs and dated many women. One evening he met a girl who was very different from those he had known before. She was young, a little bit of a devil, but smart, with the kind of beauty that comes from inner strength. Her name was Diego Rivera. Diego was hooked. They would spend the rest of their lives together. That didn't mean he wouldn't continue to have sexual liaisons with beautiful women. She left him many times, lived apart, divorced him once and married him twice. Frida finally realized that one woman would never be enough for a man like Diego. She had polio as a child, and then as a teenager, she further crippled her legs in a streetcar accident. She spent her life bound up in suffocating casts and braces. A woman who could withstand that kind of pain knew how to manage the hurt of a broken heart. She was a great painter in her own right. Diego respected her art almost as much as he cherished her love.

Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo and Delores del Rio (ca. 1932).

Edward Weston photograph of Diego Rivera (1924) Toledo Museum of Art.

Diego Rivera, seated in front of a mural depicting the American "class struggle," (1933) Library of Congress.

Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo (1926) Library of Congress.

Carl van Vechten, Photograph of Diego Rivera. (1932) Library of Congress.

Fresco Artist of the United States

By the end of 1929, the world had turned upside down. With the crash of the Wall Street Market, countries with capitalistic economies collapsed everywhere. Marx had always predicted that socialism would be born and thrive best within a highly developed industrial nation. For centuries, inequities had existed between the wealth and well-being of the few versus the poverty and ill-being of the masses. Marx theorized that in a fully developed nation, built on the principles of equality, this grievous contradiction would, finally, be so blatantly exposed, that it would drive its citizens to the development of a socialist utopia.

Diego believed the United States was the country in which these idealist dreams were about to come true. He wanted to be a part of this great world event. Amongst enormous media controversy, in 1930, Rivera, a very vocal proponent of Communism, was invited to paint a major mural in one of the bulwarks of American capitalism, the new San Francisco Stock Exchange Luncheon Club. Diego and Frida traveled to California where he painted California, based on a legend of a Black Amazon warrior queen, Califia, associated with the mythical "Island of California." Diego metamorphosed her into Mother Earth, a goddess of abundance with her giant hands gathering up the rich plenty of the State of California. This mural is, without doubt, the most gorgeous art piece he ever produced. America was in love with him.

From June to October, Diego returned to Mexico to continue working on the National Palace murals, but more importantly, he was preparing a show for the Museum Of Modern Art in New York City. His was the second one-man show to be invited to this new museum, Matisse having been the first. On November 13, 1931, Diego and Frida, sailed into New York harbor on board the SS Morro Castle. Diego was amazed at the modern architectural wonders of the soaring New York skyscrapers. After seeing California, almost immune to the depression, he was equally appalled at the despair he saw on the faces of the men, women and children standing in the breadlines and soup kitchens of New York City.

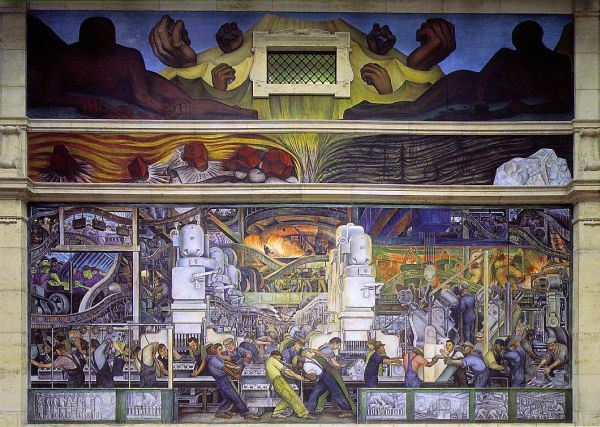

His MOMA show opened on December 23, 1931, and was a great success. More than 57 thousand visitors a month came to view his art. It had an even more popular response than Matisse. Diego loved the industrial magnificence of the United States and spent the next ten years painting his salute to it. Word quickly spread among the titans of American industry and he was asked by Henry Ford's son, Edsel, to paint a multiple paneled mural in the Detroit Institute of Art of the now famously depicted Detroit Industry Production and Manufacture of Engine and Transmission. The showing opened in March, 1933 to become an American triumph.

After the opening of the Detroit murals, Diego and Frida headed to New York City. Diego had been commissioned to paint a mural in the RCA building in the new prestigious Rockefeller Center, to begin painting on March 7, 1933. The name chosen by the architects of this complex was Man at the Crossroads Looking with Hope and High Vision to the Choosing of a New and Better Future. This daunting assignment might have made other artists decline but not, Rivera, the greatest muralist. Detailed sketches were presented by Diego and approved by the building's committee. Rivera was working industriously on the mural into April when a New York World Telegram journalist reported that Diego had inserted a heroically depicted giant head of the communist, Vladimir Lenin, in the center of the mural and had depicted the capitalist, John D. Rockefeller, martini-in-hand, on the marginal sidelines.

Detroit Industry or Man and Machine 1932-1933 (detail)

The uproar that ensued between the upholders of capitalism and the upholders of free artistic expression can still be heard in the societies of money and art to this day. Nelson Rockefeller was asked to intervene and he reasoned with Diego, and then demanded him, to replace the face on the image. Rivera, artistically always true to his personal beliefs, refused to do so. The Rockefellers paid him his full commission and removed him from the building. Months later, when the mural was jack hammered off the walls, the painter, John Sloan, declared the act "a premeditated murder of art."

In the end, when the painting was reproduced in Mexico City it was criticized as one of his worst art pieces. It could not have been worth losing his title as the grandest illusionist of them all.

His great murals were now in his past.

San Angel Studio Easel Art

In 1932, Diego and Frida returned to Mexico to move into a new dual residence in San Angel that he had built for them. The blue one was her home, connected by a bridge to the red one, used as his home studio. With the advent of film, there was no longer the need for murals to convey the messages to the people. So, Diego returned to the artist's timeworn patronage of the past, the rich. The society people wanted Riveras so he painted their portraits into Riveras.

During the next twenty years, he also painted the people who were closely entwined in his personal life such as the portraits of Christina. Once again, his art betrayed a love affair with the painting's sitter. Only this time, it was quite unforgivable, for the reason that Christina was his wife's sister and her most cherished friend. At the same time, he continued to paint Frida, clearly showing her enormous anger with him over his lusty affaires. He also painted Lupe, his first wife, who stayed close in his life because of their two children. Both women lived off and on at the Rivera home through many years. Lupe and Frida became friends and Lupe taught her how to cook to please another of Diego's huge appetites.

Late in life, Diego showed remorse for the way he had treated Frida, saying, "If I loved a woman, the more I loved her, the more I wanted to hurt her. Frida was only the most obvious victim of this disgusting trait." Throughout his life he drew hundreds of self-caricatures and painted twenty known self-portraitures, all brutally honest portrayals of himself.

Rivera's Houseguest: Leon Trotsky

Leon Trotsky was a Bolshevik revolutionary and Marxist theorist. He was one of the three leaders of the Russian October Revolution, second only to Lenin and above Stalin. When Lenin was assassinated in 1924, his death left Trotsky and Stalin vying for his vacant top power position. Stalin, being the bigger brute between the two, maneuvered himself into running the show and Trotsky ended up running for his life. He ran straight to Mexico into Diego's big welcoming arms. When the dust had settled, the idealist, Rivera, was on the side of the Marxist Trotskyites and stood against Stalin. On January 9, 1937, Leon and his wife, settled into Frida's family home that her father had built in Coyoacan. Diego turned the house into a small fortress with armed guards to assure their safety while in Mexico.

In the beginning the two families spent much time together socializing. Eventually, Diego and Leon's differing opinions on what constituted a good Marxist split them apart. Leon told Diego he was too much of an anarchist to be a true Marxist. Diego should have told Leon he was too much of a traitor to be a true friend. Would seem the ungracious Leon had a torrid love affaire with Frida while he and his wife were the Rivera's houseguests.

On May 24, 1940, Communists fired thousands of rounds into the house but failed to kill Trotsky. On August 21, 1940, a single hard-core Stalinist drove an ice pick into his neck. Trotsky died the next day. After the first attack, Rivera was in fear for his own life so he went to the American Embassy to ask for help. It seems Diego had been an informant to the U.S. State Department, a fact not uncovered until the 1990's. He got an immediate border crossing, and arrived in San Francisco in June 1940, in the company of the famous movie star, Paulette Goddard. For six months, Diego painted a live mural on Treasure Island as a showman in front of an audience. He was visited by Frida in September, on her way to New York with a lover half her age. A short while later, she returned to San Francisco to remarry Diego on December 8, his 54th birthday. When they returned to Mexico, he moved into the Blue House in Coyoacan with Frida.

Painting Till the End

The remainder of Rivera's life was a drawn out length of sadness. Frida died at age forty-seven on July 13, 1954, in great pain, with one leg amputated. Life without Frida was no good for Diego. Six months later, he was diagnosed with cancer. He married his art dealer, Emma Hurtado, and went off on a long tour of Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union.

After returning to Mexico City, he went to the Hotel Del Prado to alter the famous mural he had painted there in 1947, Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park. The owners had to have a special drapery made to cover the mural and through the years it was only viewed by special request. On April 13, 1956, he finally painted over the words he had so often refused to change during the past ten years, "Dios no existe." On April 15, 1956, he called a press conference to announce to his Mexican people, "I am a Catholic." He was turning toward home.

Modern art had moved into abstract imagery, altogether devoid of identifiable form. Critics who had so acclaimed his art, now looked at his ideological paintings almost embarrassingly. Still, Diego painted to the end of his life. He died at the age of seventy-one, painting in his studio, on November 24, 1957.

The easel work done in the last part of his life is the most enduring of Diego's paintings. These are the pieces that are most recognizable and collected today. Many are still copied and reproduced today in book jackets, cards and poster art. His last paintings were of the indigenous people of Mexico. He portrayed them in the rhythmic movement of their everyday lives. They were the other most consistent love of his life, the true citizens of his Mexican landscape.

Diego Rivera was believed to be, by many of his contemporary artists and art critics, the finest artist of the 20th Century.

Contact Us

Examination - We are equipped to examine Rivera paintings and drawings globally, wherever it is safe to do so. Our team can assess your Rivera artwork at a variety of locations, including your home, office, bank, attorney’s office, restorer’s studio, art storage facility, hotel, or even on your plane or yacht while you’re traveling. We can also conduct examinations at art galleries or auction houses if you are considering purchasing a Rivera. Additionally, we offer examination services at the offices or facilities of government agencies, law enforcement offices, universities, libraries, financial institutions, museums, religious organizations, and other institutions. For liability and insurance purposes, we do not conduct examinations at our own premises.

Email:

info@riveraexperts.com

Phone:

+1 (332) 233-9665